For a couple of months last year, my wife and I found ourselves homeless.

Let me explain: We had sold off our flat, but our new place wouldn’t be ready for another few months. One option was to rent, but seeing how crazy rents in Singapore were, we asked ourselves: Wouldn’t it be cheaper to live and work from Bali?

Ever since Tim Ferriss’ published the 4-Hour Workweek in 2007, I’d been fascinated by the idea of digital nomadism. What would it really be like to live in an exotic location, meet interesting people, have adventures in a foreign land, while earning your keep using just a laptop? It’s the archetypical Millennial wet dream of living a life of experiences over possessions.

The pandemic has only accelerated this trend. The Lufthansa Innovation Hub found that Google Search combinations for “digital nomad + country” have increased by +69% in the past two years. COVID-19 showed that a lot of work doesn’t have to be done in the office, so why not take the opportunity to escape the office and do what you love the most – travel?

Now, I have a full-time job which requires me to be in the office 3x a week. Thankfully, my company also allows us to work from anywhere for 4 weeks, to “give flexibility around summer and holiday travel.” Therefore, I could legitimately work from Bali, as long as my manager said yes and that I still continued to produce results. My wife has a similar arrangement at her company as well.

So we planned to live in Bali for 6 weeks: 4 weeks of work, plus 2 weeks of vacation. That would be just enough time to live a digital nomad lifestyle without committing to a costly multi-month lease. To be honest, I had mixed feelings about this adventure. Would we be bored being stuck in one location, away from our family and friends? Would we like the food? Would the wifi suck?

This is what we found out.

(Caveat: Travel is a uniquely subjective experience. Your friend might love a place and you might hate it, simply because you both have very different preferences and therefore choose different experiences. So a lot of what I’m about to share are based on my VERY subjective experience and biased opinions. Some of you might argue that I can’t call it “digital nomadism” if I’m living in just one location for 6 weeks . Therefore, take what’s useful and leave what’s irrelevant to you.)

Where We Stayed

We chose to base ourselves in Canggu, which has recently become Bali’s unofficial digital nomad hub. Virtually every restaurant and cafe had strong wifi. Our co-living space connected their wifi to a backup generator, so whenever we had a blackout (which was a pretty common occurrence), the lights and aircon in the entire street would go off, but the wifi would remain faithfully chugging along.

We considered various accommodation options including Airbnbs and private villas, but in the end, we opted for a co-living space where everyone gets their own room, but shares the facilities such as the kitchen, pool, and coworking space. Ever since college, I’d loved the dorm experience and always wondered what it would be like to live in a “dorm for adults” space like lyf or Hmlet in Singapore.

One key reason for choosing a co-living space was because we wanted to meet other digital nomads. We wanted to understand their worldviews, learn from them and be inspired by them. Also, as natural introverts, we also wanted to force ourselves to make friends, which would help stave off the inevitable loneliness that would come after 6 weeks of being away from family and friends.

After a lot of research and deliberation, we eventually opted for Outsite, because (and this is my spoilt Singaporean talking) it looked like the nicest, most comfortable one. It also looked big enough that I knew I wouldn’t be taking my work calls next to a sweaty, shirtless drunk tourist. Here are some pictures:

Living Conditions

Bali is one of those places that looks super Instagrammable from afar, but when you zoom in it’s a little rough around the edges.

For example, our accommodation featured a lovely outdoor bathroom, and I envisioned myself showering under the stars while listening to the calming sounds of nature. But in reality, every shower is like a NatGeo documentary: We were constantly in the company of dragonflies, butterflies, beetles, frogs, millipedes, and a lizard the size of a pigeon which terrified my wife.

While taking an early morning stroll around the villa, one of the guests spotted Mollie, the resident monitor lizard, taking a lovely swim in the pool:

Pooping in the bathroom also became a Battle Royale of Lionel vs. Mosquito, where I do my best to swat as many commando mosquitoes while remaining seated. On the plus side, I no longer wasted 30 minutes in the bathroom so I became a lot more productive.

Thankfully, the air-conditioned rooms were (mostly) spared from insects as long as we had the electronic repellents on. The rooms were luxuriously huge – there was just so much space. Our single room occupied more square footage than our future condo. The sprawling grounds had plenty of room for guests from all 7 rooms to work, swim, lounge, and dine.

Don’t get me wrong about the living conditions: While I make it sound like the Hunger Games against nature, it was still a massive privilege to live in such a beautiful space. Just don’t expect it to be the Ritz-Carlton.

The Lifestyle

There’s something about Bali that makes you wake up early. I routinely struggled to get up by 7am in Singapore, but I had no problems getting up by 6am in Bali. Maybe it’s because the sun rises earlier in Bali. Or maybe it’s the whole avocado-for-breakfast-yoga-by-the-sunrise-namaste lifestyle that gets everyone out and about super early.

Anyhoo, getting up at 6am gave me enough time to start the day slowly. I’d make coffee, and sit facing the pool to pray, reflect, and do some writing. Even after all that, I could still start work by 8am and get ahead of the day.

The rest of the morning would be typical work stuff: I’d build decks, take calls, argue with teammates, and pitch clients. While I definitely had less interruptions, it came with all the trappings of remote work that we hated during Covid: Back-to-back video calls, instant messaging simple questions (“Hi I hope you’re doing well I just had a quick question”), and spending all my time scheduling meetings.

Lunch might consist of babi guling, burbur ayam, or mie bakso delivered via the insanely cheap GoJek food delivery, or we might scoot out to a nearby cafe or warung to eat. Unfortunately, work was still super busy so I wasn’t having leisurely 2-hour lunches in some Instagrammable cafe. Evenings were better: I’d end work by 6pm, and we’d scoot 4 minutes to Pererenan Beach to enjoy some of the most amazing sunsets I’d ever seen:

On the weekends, we’d take side trips out to visit other parts of Bali like Ubud, Seminyak, Uluwatu and Nusa Dua. There, we’d check out the beach clubs, dine at lovely restaurants, and shop. Massages were amazing and less than half the price of Singapore, so we would have one every week. (This place was our favourite!).

Notice what we didn’t do though: We didn’t surf, or go to parties at Finn’s, La Favela, etc. I’d tried surfing once and it was way too much effort, and we’re kind of done with the party scene (especially in any place filled with rabak shirtless people). I appreciated having the time to blog, read, make plans for 2023, watch the sunset, and have slow conversations with my wife. It’s a wonderful feeling to actually be leisurely on the weekends, in contrast to my normally-frenetic schedule in Singapore.

To be honest, I didn’t do a lot more than what a typical tourist might do during a 5-day trip to Bali. Because work occupied much of the week, and because we took things super slow, the total quantity of experiences we had wasn’t exceptional. The only difference was that we did things at a leisurely pace.

Perhaps a little too leisurely: we found ourselves getting restless around the last week, itching to go back to Singapore where there would be people to meet, events to attend, and drinks to toast. It also confirmed what I’d suspected all along: That retiring early on the beach with a drink and book in your hand is essentially a mirage – I could do that for awhile, but after a month or so I’d be so bored that I just might jump back into activity.

Getting Around

Let’s just call it like it is: Bali’s infrastructure is bad.

Traffic jams are a way of life. Often, a jam comes about simply because everyone is trying to navigate their way through a cross- or T-junction with no traffic light. Scooters would cut their way in, weaving against the flow of traffic, while the big lumbering cars would have no choice but to inch forward wherever they found space.

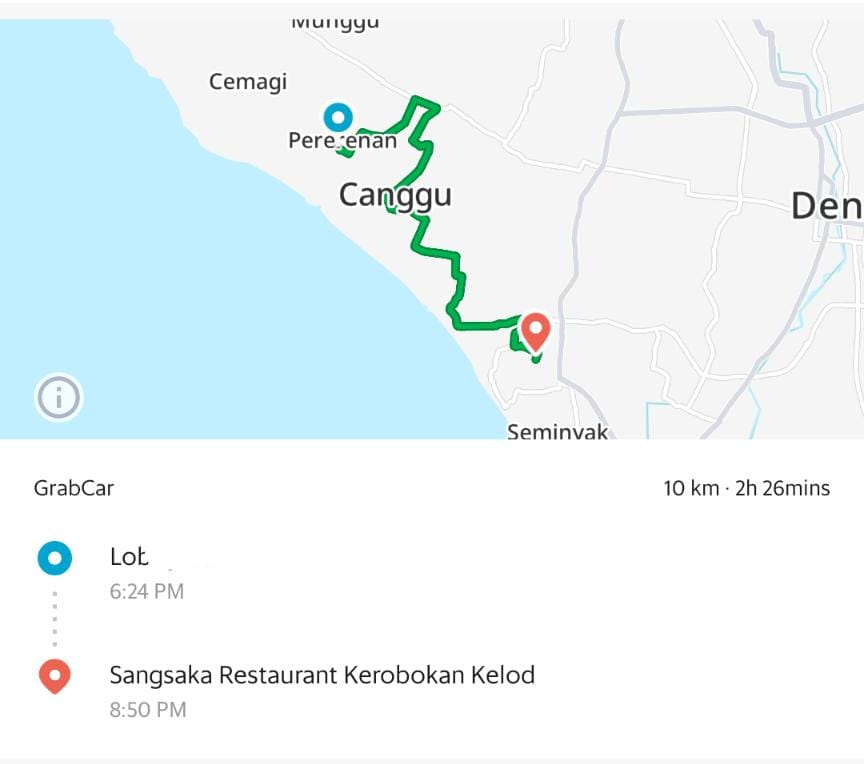

Here’s a screenshot of my Grab ride from Canggu to Seminyak, which was a mere 10km away but took 2.5-frickin’ hours to travel:

I don’t know how Grab drivers make money if they’re constantly stuck in traffic jams, earning S$10 for an entire night’s work. To their credit, they never grumbled even though they were probably making fun of these dumb tourists who would waste so much time in a car. So I’d normally give them a big tip for sticking it out with us.

However, calling a Grab or a GoJek is also a test of patience. Often, my order would be quickly accepted, only to have the driver not move for 15 minutes. It drove me nuts when we first arrived in Bali, but I learnt to let it go. Now, we simply budget for an additional 30 minutes to 3 hours to account for uncontactable drivers, unexpected jams, and everything else in between. I learnt to simply shrug and go “ahhh, it’s Bali” and then let it go. Not a bad philosophy to apply to life in general.

Having said that, I’m not sure if I could live with this for the very long-term. Maybe I’ve been spoilt by the efficiency and the infrastructure of Singapore. These are things that are invisible and are so easy to take for granted, but once they’re taken away I realise how much I’d been relying on them. On the way home from Changi Airport, cruising down the lovely wide expressways, also made me extremely grateful for how amazingly well-run our country is.

The People

As I mentioned, we stayed at a co-living space because we wanted to meet new people. Specifically, we wanted to meet folks who were outside of our Singapore bubble. We wanted to encounter people who didn’t subscribe to the graduate-buy-HDB-get-married-work-at-a-PMET-job-have-kids-retire-take-out-CPF way of life.

And we did! Co-living gave us the opportunity to have random conversations in the kitchen and the dining area. Pande, our amazing community manager, regularly organised group dinners where anyone (including former guests who were still in Bali) could join. As a former chef, he would harvest banana trunks from the garden and whip up meals which were tastier than the Michelin Star restaurants in Seminyak. For example, here’s what he set up for Christmas:

Here’s what fascinated me about the people we met: While they were from all walks of life, everyone had pretty much embraced the remote living lifestyle. They were coaches, freelance engineers, consultants, nutritionists, travel planners, and agency managers. But they all agreed that it’s better to introduce a little instability into their lives in exchange for the freedom to explore the world. It was a vastly different worldview compared to the typical Singaporean who prioritises efficiency and stability (again, referencing my above comment on the traffic).

There was Nathan & JB, two French software engineers so brilliant that they could negotiate any salary they wanted, allowing them to travel for six months for every three months of work. There was Anish, who moved to Portugal so that he could manage his video agency completely remotely. There was Andrew, a time management consultant who spent 6 weeks in Bali finishing his book. There was Georgie from Australia, who ran her calls from her bedroom, coaching women on high-performing anxiety.

And there was Ricky and Sarah (hi Ricky and Sarah!) a couple from New York who decided to work and travel for 3-5 weeks at a time in each country, for an entire year. They often had no idea where they would be in a month, and Sarah would regularly book their onward flight while they were in the airport check-in line, so that they would be allowed to into the country.

We hit it off with Ricky and Sarah. Maybe because they were Asian, so we could understand each other culturally, but they were also just one of those people who asked really deep questions and gave really self-aware answers. Maybe the world does have interesting people after all.

Friendships

Ricky and Sarah were the exception though. Maybe it’s because I’m introverted, but I found it really hard to form real friendships while living in Bali. Sure, we met a lot of people, but I found it hard to really connect on a deeper level. Maybe the reason is cultural: I found myself needing to explain cultural references and norms which seemed obvious to us but perplexing to others. For example, the Europeans couldn’t understand how Singaporeans could tolerate having just one political party governing us for decades, which seemed like a travesty to them.

Maybe we couldn’t make deeper friendships because people were so transient. Or maybe we just didn’t put ourselves out there as much as we could have. But in general, aside from Ricky and Sarah, my wife and I didn’t have sustained friendships with people beyond the first few conversations. It was nice, because my wife and I got to spend more time with each other. We connected more deeply and had the luxury of simply “wasting time” together – like watching the entire Season 2 of Alice in Borderland. (I don’t care what anyone says, I think the plot had an excellent ending which tied everything together and explained the whole setup in a satisfying way).

But I also wonder about the tens of thousands of people who move to Bali alone to find themselves or embark on an adventure. It takes remarkable courage to be in a new place, all alone, needing to build friendships from scratch. All that, while navigating the cultural and logistical complexities of moving to an entirely new location. I absolutely agree with the accounts of other digital nomads, who’ve found that loneliness is probably the most difficult challenge to navigate.

But perhaps that’s the price of entry. By definition, a nomad is one who is transient, and as a consequence has a larger physical and emotional distance from their friends and family back home. So that’s perhaps the flip side of freedom, one where you might have to trade off friendships, or at least work a lot harder to build them.

What I Learnt

My One Big Lesson was that adventure/freedom and community/rootedness are two sides of the same coin.

My six weeks of living a different lifestyle and meeting other nomads was an eye-opening experience. But it also confirmed my suspicions that being permanently remote isn’t as appealing as what Tim Ferris or Instagram makes it out to be. There are definitely tradeoffs, especially in the areas of efficiency, friendship and community.

Having said that, I think that most people would benefit from living/working remotely at least in some capacity, even for a couple of weeks. It definitely helped me to see beyond my safe, sanitized Singapore bubble. 6 weeks of remote living was a little too long for Bali, but 4 weeks might have been perfect.

Just make sure you bring along that mosquito repellent.