I left Singapore to study in the US when I was 21. In my freshman year, I met all sorts of people in my dorm. I was neighbours with a football jock, a math champion, wannabe gangsters, and ambitious pre-meds. They had all sorts of wacky hobbies, from skateboarding to deconstructing Rubiks cubes to swing dancing.

But something weird happened when I got to my senior year: Everyone set aside their unique quirks, dressed up in the same business suits, went for the same networking events, and applied for the same internships. For all the diversity of my freshman class, the majority of my friends ended up in the same two industries: banking and consulting. What was going on?

The answer, I think, lies in the philosophy of a French Social theorist named Renee Girard.

Renee Girard and mimetic theory

Girard is most well-known for his theory of mimesis. Paypal co-founder Peter Thiel was one of his students. Thiel’s book Zero To One draws heavily from Girard’s philosophy (although Thiel never explicitly mentions Girard by name).

Once I read about mimesis, I saw it everywhere: in my friends, my work, in business, in relationships and in politics. It’s one of those all-encompassing worldviews that explains a lot about almost everything.

So what is mimetic desire? Girard believed that our desires aren’t independent or autonomous. Instead, we want things just because other people have them. Because we don’t know what we want, we end up imitating other people instead of coming up with our own desires. We are essentially highly-evolved sheep.

Maybe you’ve never been a big fan of cycling. One day, your friend Sam tells you about this fancy new bike that he just bought. Suddenly, you start noticing the same fancy bikes everywhere, and slowly your desire grows until you eventually buy one yourself. You tell yourself that you have good reasons for your purchase: It’ll help you to exercise more, it’s a great way to spend time with family, and you’ve always wanted to pick up a new hobby anyway. But Girard would say that the real reason you wanted it was because Sam had it in the first place.

Mimetic desire doesn’t just apply to bicycles, it can apply to anything, including the jobs we want.

How my friends and I fell into mimesis

“Man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do.”

Thomas Jefferson

In college, I would sometimes travel to New York to visit friends who were working as investment bankers or consultants. I’d admire how they were living my “dream” life: Living in their own swanky apartment with a doorman, opening bottles at clubs, and dining at fancy restaurants. I so desperately wanted to live the same life as they did, that I even contemplated breaking my scholarship bond (Thankfully, my parents talked some sense into me).

Girard believed that any desire beyond basic needs (like food, water and shelter) are metaphysical. That is, we want something not because of the thing itself, but because of what it represents. You buy a Mac not just because you can surf the internet and play games, but because it represents you as the kind of person who uses a Mac.

In the same way, I wanted to live the New Yorker banker/consultant life not because I was particularly interested in building discounted cash flow models, but because of what I imagined that the job would say about me. And I built that ideal version in my head by imitating the lifestyles of my New Yorker friends.

The thing about college is that everyone is in such close proximity, so you’re constantly reminded that all your friends are applying to the same jobs, which reinforces that desire. This causes you to apply to the same jobs, which reinforces their desire, creating a self-perpetuating loop of mimetic desire.

Why tech became popular

All of this happened back in 2009 / 2010, before it was cool to get a job in tech. Since then, the tech sector has surged ahead in popularity among jobseekers. Information Sciences used to be a safety school for people who couldn’t make it into business, law or medicine. Now, computing is among the top 5 most popular university courses in Singapore.

While there were a lot of factors that contributed to the rise of tech’s popularity, two events made it concrete for me: 1) I watched The Internship, and 2) I was invited to visit Twitter’s Singapore office in 2015.

In The Internship, I marvelled at Google’s colourful campus with slides and nap pods and free snacks. When I visited Twitters’s office, I got super excited that you could show up to the office in jeans and a t-shirt. I know this sounds wonderfully quaint reading this in 2022, but 7 years ago this was a real novelty to me.

I told myself that I would eschew the outdated trappings of a traditional corporate job, and embrace this “new frontier” of a career. When I finally made it into the tech industry, I remember feeling smug as I stepped into the elevator in my t-shirt and jeans, surrounded by buttoned-up suits from other offices. Yes! I had finally broken free of mimetic desire of the corporate world!

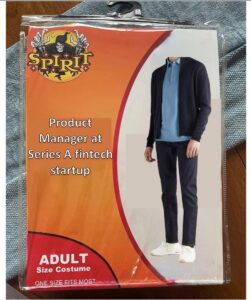

Unfortunately, that wasn’t true. Girard would say that my foray into tech was simply a continuation of my mimetic game. Those who joined tech tried to be the antithesis of the corporate world, but as more and more people joined, that too eventually became mimetic itself. Now the “tech uniform” is so mainstream that it’s become a meme:

So how can we escape mimesis?

According to Girard, there is no end to desire. As soon as it becomes detached from one thing, it immediately looks for another model to attach itself to. This doesn’t just apply to bicycles or jobs, but to any desire.

We’ll never be able to fully detach ourselves from mimesis since it’s so ingrained in our nature. Nor is it necessarily always a bad thing. Mimesis can push us to be inspired by others and achieve great things. Furthermore, our sociality and our ability to relate to other people is a big part of what makes us human.

But the key lesson is to simply be aware: Why do you really want what this job, this car, or this holiday? How much of it is actually because someone else – a friend, a colleague, an influencer – has it?

I’ll leave you with this. In his tribute to René Girard on his 70th birthday, Robert Hammerton-Kelly wrote about how our mimetic desires stem from the void in our hearts:

“the void drives us to seek fulfillment from our fellow human beings, whom we mistakenly believe to possess the ontological fullness that we lack. Thus we fall into a war of desire for empty prestige and hollow pre-eminence.”

Girard believed that all desire is, by its very nature, transcendent. While we might be tempted to search for transcendence in “empty prestige and hollow pre-eminence”, perhaps we should direct them to something else, something larger beyond ourselves.