When I was in college, I was an obnoxious smartass. Like every ambitious, testosterone-driven Singaporean male, I believed I could trade my way towards becoming a millionaire.

When I was in college, I was an obnoxious smartass. Like every ambitious, testosterone-driven Singaporean male, I believed I could trade my way towards becoming a millionaire.

So I bought some trading software, some market data, several hundred dollars worth of trading books, and begin to craft my own strategy. Back then, “rules-based” technical trading was all the rage. I coded these rules into my software, making my trading model complex, layered, and sophisticated.

In my backtest results, the model performed wonderfully. It was projecting a 5% returns per month, which would make me a millionaire in less than a decade. Armed with statistically-significant data, I started trading with “seed funding” from my parents…

… And it was a total disaster. I lost over $10,000 in a few months – an exorbitant amount of money for a poor college kid.

What went wrong?

I Committed The Overfitting Fallacy

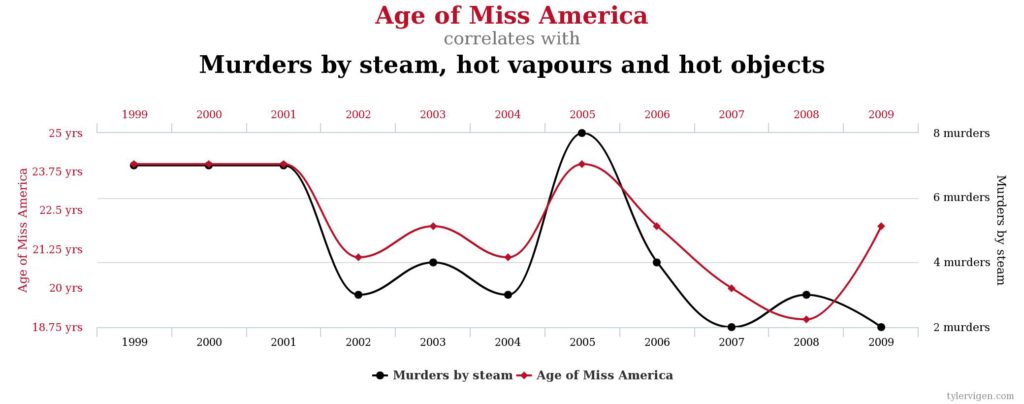

The Overfitting Fallacy happens when you build a model or strategy that overfits past data. For example:

Credit: Tyler Vigen (click to see more hilarious examples of spurious correlations)

However, apply that same model to new data, and it completely breaks down.

I once attended a trading seminar where this forex guru presented his proprietary trading strategy that has never had a losing month. His strategy? Something along the lines of “Always buy on the 3rd Tuesday of every month when the stochastic moving average is above its 27-day average.”

It’s true – when you backtest that strategy, it has indeed never had a losing month. But how did he arrive at that conclusion? By trying out different combinations of parameters until he found the one that worked beautifully in the past. But try applying that same strategy to new data, and you’ll probably see very different results.

Smart people are ESPECIALLY susceptible to the Overfitting Fallacy, especially when they get their hands on data.

Overfitting In Investing

Today, retail technical trading has more or less been discredited. But the Overfitting Fallacy has simply moved from trading over to investing.

Lots of firms and ETFs now promote their supposedly “market-beating” services, showing off fantastic backtest results to lure investors in.

For example, one REIT ETF has the aim of “enhancing returns above that of traditional market-cap weighted ETFs”. Having backtested the returns, they show splendid returns of 9-10% per annum for the past 5 years.

Other firms also use their “Nobel Prize-winning methodology” to help construct your ETF portfolios, allocating 6.2% into your Consumer Staples ETF, another 0.7% into your Gold ETF, and 17.8% into your Japan ETF.

I totally get why this sounds really smart and sexy. It’s human nature to want to see a “track record” and be lured by past performance. But remember that one disclaimer they always put at the bottom: Past performance does not indicate future performance.

This is ESPECIALLY true when it comes to investing!

How Can Investors Avoid The Overfitting Fallacy?

I love this example from Harry Markowitz, the founder of Modern Portfolio Theory himself.

Using sophisticated mathematics, he came up with the optimal way to construct a portfolio of stocks and bonds to maximise returns and minimise risk. It’s a brilliant model, and certainly impressive enough to win him the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. (This is the same “Nobel Prize-winning methodology” that so many investing firms use today)

But as Tim Harford writes in his new book Messy (which I’m really enjoying):

“There’s a funny story about Markowitz, though: shortly after publishing his theory, he started a job with a retirement savings plan and he had to decide on the optimal blend of investments for his own retirement.

This was the perfect opportunity to put his brilliant new theory to use. He passed up that opportunity and instead, put half of his money in stocks and half in bonds.”

Think about the irony: The CREATOR of Modern Portfolio theory didn’t have confidence in his own models when investing his own money. Instead, he opted for a much cruder strategy of 50% stocks, 50% bonds.

Why? Because in the face of an unknowable future, we’re better off sticking with simple strategies.

Many of us could learn from Harry Markowitz’s example when it comes to our own investments:

- Instead of trying to pick undervalued stocks, just buy the entire market

- Instead of building overly complex portfolios of commodities, short-term bonds, emerging market bonds, etc, just build a simple, diversified portfolio with a couple of stock and bond ETFs

- Instead of deciding the “optimal” time to buy and sell, just dollar-cost average slowly into the market

I’m not saying that data isn’t important – it is. But in a domain like investing which is inherently random and uncertain, it’s possible to be over-reliant on the data.

Personally, I’d pick the laughably simple strategy of passive investing any day. This gets nothing but yawns from your friends and your crazy gambler uncles, but it works.

Good one, Lionel.

And what those gurus often forget to mention: it’s always what we do after we have bought a stock / ETF that makes a much bigger difference than finding the right entry (still people do spend so much time on this single – not decisive – aspect of investing).

I’m on your side but you should also probably read the book by James O’Shaughnessy titled What Works on Wall Street. It’s a comprehensive study over 52 years of the stock market history and what he found was that certain stocks DO outperform the “market”.

Basically, an index works because it doesn’t deviate from its rules. The STI is the 30 largest stocks in Singapore, the S&P500 is the biggest 500 in the US stock exchange. And stocks with certain characteristics can also form an index of their own, and some of these indices have better long-term returns.

If people work backwards from the results to reach the methodology then yes, this falls in your overfitting fallacy. But if you start from a rationale standpoint and then see if this makes sense over 52 years of history, then it doesn’t and that’s what the author did.

For example, do “value” stocks outperform the market? And the question is “yes” together with some other characteristics he found. It’s the same with studies that show that the lowest P/E stocks give the highest returns, and low price-to-book stocks with high Piotroski F scores also beating the market.

Just wanted to offer an alternative viewpoint for you and your readers and that not all backtesting suffer from hindsight bias or a overfitting fallacy. Another usual study is by Tweedy and Brown titled What has Worked in Investing. Worth a read.

Totally get the perspective – the basis of index investing doesn’t say that it’s impossible to beat the market, only that it’s extremely unlikely to do so in advance.

There are definitely studies showing that certain profiles of stocks DO beat the market over the long run, as you pointed out. But if value investing, for example, is such a well-established market-beating strategy, why are there so few investors who had successfully taken advantage of it?